I took a flight across the Atlantic from my house in London to visit my wife in Costa Rica. In 2014, while staying in Bordeaux, France, I last flew. Going by train to the hen party of my sister in Scotland, my usual choice, It took me days I didn’t have, so I also bit the bullet and took a flight.

His strong carbon footprint is the reason I have stopped flying for so long. Since I was a teenager, I would have had a growing niggling shame over flying pollution when I thought about climate change and its implications more and more. After all, traveling on an hour-to-hour basis is potentially the most carbon-intensive thing you can do. This eventually led me to promise to do it only if it was necessary.

And I’m not alone with that. The anti-flying campaign known as “flight guilt” – or flygskam in Swedish, where the movement started – has gained momentum in Europe over the past year or so.

The term refers to the guilt of flying at a time when the world needs to cut greenhouse gas emissions dramatically. To me, this indicates a disturbing comparison between a weekend’s happy-go-lucky indulgence and the devastating impact of climate change on the real world. Others referred to it as the humiliation of traveling instead of being “woken up” in the city.

This increasing resistance to aviation has given renewed momentum to rail travel, with some rediscovering the attraction of night trains, and increasing pressure on politicians to address the climate impact of aviation.

Yet our ideas about how, why, and where we are going are also changing.

While “shame” is a very derogatory term, the goals are positive –both for those involved in the initiative and for the community. Importantly, it’s less about riding “shame” other people than changing your habits of travel.

Therefore, the aim of many traveling less is by no means to discourage people from exploring the world. “Not boarding means not moving,” says Anna Hughes, who runs the UK movement for Flight Free 2020. “There are so many places we can use other means to access.”

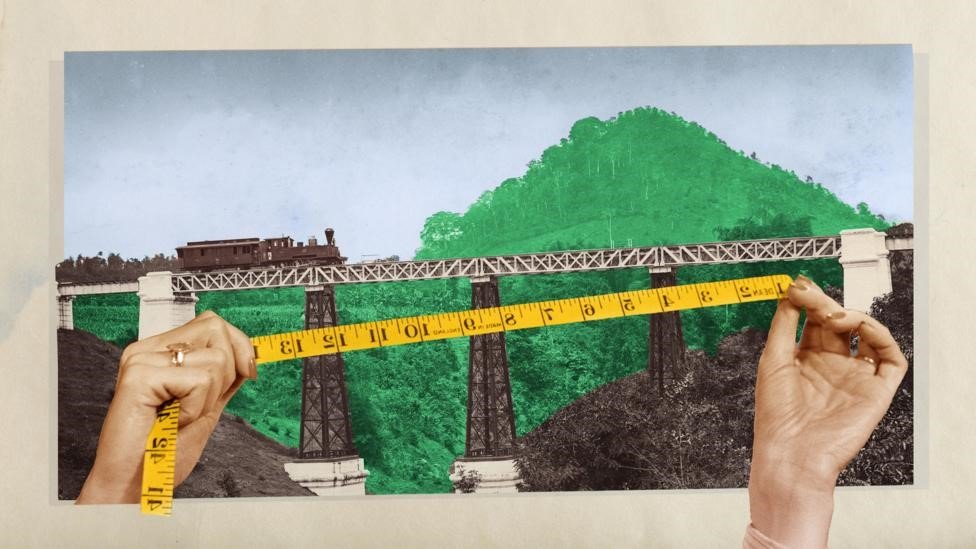

Alternatively, the campaign is about reveling in the long, careful journeys without aviation that are possible. Train travel is one of the obvious choices, with one-10th of flying pollution, says Hughes. “And it’s much more fun from my point of view,” she says.

It’s easy to forget that a plane isn’t always the fastest or cheapest option since train travel typically takes you from one city center to another. High-speed trains, in particular, have enormous potential as an alternative: new high-speed lines have been shown to reduce air transport by as much as 80% on the same routes.

And even if it takes more time, it can be more convenient for other forms of transport. Like Hughes, in my five earth-bound years, I have known the joys of slow travel, From late-night talks with a few Iranian travelers on the overnight train to Verona to sipping whiskey at the Caledonian sleeper’s bar in Edinburgh.

Nor will slow travel be restricted to short distances. Roger Tyers is a climate sociologist who recently returned to China from a “no-flying field trip,” which took him two weeks one way by train. It may sound like a daunting expedition, but about his train journey, he’s glowing. “It’s been an exciting journey,” he says. “I saw some amazing things you just wouldn’t see getting on a plane.” He lists a slew of other benefits: remote detox, blogging, chatting to various people, no jetlag. “And just admire the beauty and existence of our world.”

So place the contrast between train and airline in perspective, you only need a return flight from London, so Moscow to use one-fifth of your “carbon budget” for the whole year. This target is the amount of carbon that can be generated by every human in 2030 while reducing dangerous levels of global warming. Having the same train journey will take approximately one-50th of your annual budget.

However, if you include the warming effect of pollutants other than CO2, such as water vapor in contrails and nitrogen oxides emitted at high altitudes, the results of aircraft pollution are believed to double at least. Because of the larger seats, it triples again if you take business, not economy classless efficient use of precious cabin space. (Find out what air pollution can do for your brain.)

“The more you understand the impact of travel on the atmosphere, the more you feel guilty for getting on a plane,” Hughes says.

Once Swedish singer Staffan Lindberg revealed his decision to give up travel, the flight shaming campaign first appeared in 2017. Some influential supporters include biathlete Björn Ferry, who has vowed to qualify to participate, and opera singer Malena Ernman, mother of 16-year-old climate protester Greta Thunberg.

The proposal has gained the most traction of Sweden so far. Hashtag #jagstannarpåmarken has become a buzzword, which translates as #istayontheground. There are 60,000 followers on an Instagram page asking for celebrities advertising travel to far-flung destinations. Thunberg’s own efforts to avoid flight also raised the movement’s popularity even further and earned several areas of fierce scorn.

It seems that the idea has already had a measurable impact on Sweden’s travel patterns. In the first three months of 2019, airport operator Swedavia AB saw passenger numbers fall year-on-year across its ten airports. Swedavia says the climate debate is one reason for a 3 percent drop in the name of domestic passengers in 2018. According to a WWF survey, a total of 23 percent of Swedes reduced their air travel in 2018 due to their climate impact.